Cognitive Bias and the Design Process, Part 1

Designers are just as vulnerable to the blindspots and fallacies that come with cognitive bias as the people who use the products and services we design. Bias can creep into the design process when we aren’t diligent enough to identify and mitigate it upfront. A big part of avoiding this is by cultivating awareness of when and how they can be introduced into the design process and influence design decisions.

This article explores a few cognitive biases I’ve experienced first-hand as well as strategies for mitigating their influence. These biases are by no means the only ones that I think designers should be aware of – there are many, many others as well. That being said, I think these are the most common ones that designers must deal with during the design process. They are also the ones that have the potential to influence design decisions the most, which ultimately impact the products and services we help to build.

Consider What You Don’t See

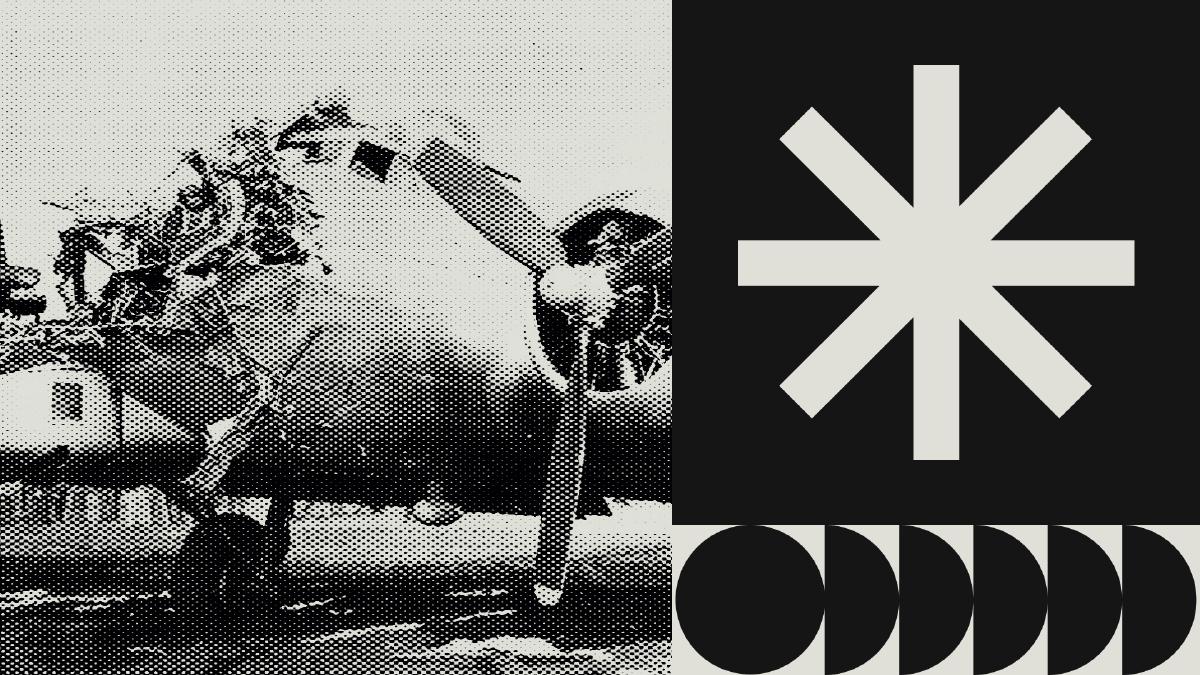

During World War II, the Statistical Research Group at Columbia University was asked by the U.S. military to examine the damage done to bombers that had returned from missions. Their objective was to determine where armor could be added to the bombers to increase the protection from the flak and bullets. Planes that returned were carefully examined and damage was compared across all the planes. The consensus was that additional armor should be added to the areas of the planes that show the most common patterns of damage: the wings, tailfin, and middle of the planes.

Luckily, a statistician on the project by the name of Abraham Wald countered this conclusion by pointing out that the planes being examined were only those that survived, therefore calculations were missing a critical set of data (the planes that didn’t make it back). As a result, Wald recommended that armor get added to the areas that showed the least damage to reinforce the most vulnerable parts of the planes.1

The case study of World War II bombers highlights our tendency to concentrate on the people or things that made it past a selection process and overlook those that do not, typically because of their lack of visibility. This can lead to false conclusions in several different ways. This tendency is known as survivorship bias and it can show up during a critical part of the design process.

How it occurs

Research is a critical part of the design process because it forms the backbone of understanding in regards to end-users and how the product or service we’re designing will fit into their lives. The data we receive during this time is fundamental to the success of a project — as it helps to guide subsequent design decisions. One critical way that survivorship bias can creep into the design process is through the participants we choose (or leave out) of design research. A lack of participant diversity will inevitably lead to a lack of data diversity. If you’re only considering one perspective, it will reduce the reliability of the data.

Design feedback is another crucial part of the design process and also one that survivorship bias can take hold. The best design is that which considers a diversity of perspectives, specifically in regards to the people who will be using it. For example, focusing too much on only the positive feedback from our peers is likely to result in solutions that aren’t resilient enough. If the team with which we are receiving feedback lacks diversity, so will too the input we receive during the design process.

Factoring in failure

While survivorship bias is common within the design process, there are ways to counter it as well. When we focus too much on success stories, positive metrics, or ‘happy paths’ in our designs, we lose sight of how the design responds when things fail. Consideration of only positive feedback is likely to lead to a very one-sided design approach. It’s best to factor in failure, consider where things can go wrong, centralize the edge cases in the design process, and seek out diverse perspectives during design reviews. In other words, we can make our designs more resilient by considering the unhappy path just as thoroughly as the happy one. In the process of designing for the less ideal scenarios, we address the fundamental features needed for everyone.

Recognize the limits of quantitative data

We must remember quantitative data is only relevant to the actions currently available and therefore has the potential to limit our thinking. As Erika Hall points out in Just Enough Research, “By asking why we can see the opportunity for something better beyond the bounds of the current best”.2 We should consider what the quantitative data isn’t telling us to make more informed design decisions.

Related

Sampling Bias

A bias in which a sample is collected in such a way that some members of the intended population have a lower or higher sampling probability than others.

Availability heuristic

A mental shortcut that relies on immediate examples that come to a given person’s mind when evaluating a specific topic, concept, method, or decision.

Don’t build solutions in search of a problem

People who hold strong opinions on complex social issues are likely to examine relevant empirical evidence in a biased manner. As a result, they will accept confirming evidence at face value while critically examining evidence that disconfirms their opinions. This was the conclusion of a study conducted in 1979 at Stanford University concerning capital punishment.3 In the study, each participant read a comparison of U.S. states with and without the death penalty, and then a comparison of murder rates in a state before and after the introduction of the death penalty. The participants were asked whether their opinions had changed. Next, they read a more detailed account of each comparison’s procedure and had to rate whether the research was well-conducted and convincing. Participants were told that one comparison supported the deterrent effect and the other comparison undermined it, while for other participants the conclusions were swapped. In fact, both comparisons were fictional.

The participants, whether supporters or opponents of capital punishment, reported shifting their attitudes slightly in the direction of the first comparison they read. After reading the more detailed descriptions of the two comparisons, almost all returned to their original belief regardless of the evidence provided, pointing to details that supported their viewpoint and disregarding anything contrary. The results illustrated that people set higher standards of evidence for hypotheses that go against their current expectations.

We tend to search for, interpret, favor, and recall information in a way that confirms or supports our prior beliefs or values. This tendency is known as confirmation bias, and when we aren’t careful it can also show up during the design process as well.

How it occurs

Generally speaking, we can be susceptible to confirmation bias whenever we seek information. One place we can anticipate it showing up throughout the design process is during user testing. For example, focusing on test findings that validate the desired outcome. Another way confirmation bias can find its way into the design process is through design feedback. Similar to survivorship bias, the best design is that which considers a diversity of perspectives, specifically in regards to the people who will be using it. This is also an important consideration with confirmation bias, where we can block out or become more critical when receiving feedback that doesn’t validate or support the design direction we’d prefer.

Multi-faceted user research

You’ve probably heard the saying “pay attention to what users do, not what they say”. User actions and feedback is seldomly aligned, and this can introduce inaccurate data in the design process if we rely too much on user feedback alone. Feedback is great for understanding user thinking, but not great for understanding their actions. One way to combat the confirmation bias is a multi-faceted approach to user research. Using a combination of user interviews, usability testing, and quantitative analysis to understand peoples’ actions will help to avoid the bias that comes with overly relying on any single method.

Red Team, Blue Team

Another effective approach to combating confirmation bias is to designate a separate team (the red team) to pick apart a design and find the flaws. In his book Designing for Cognitive Bias, David Dylan Thomas points out the effectiveness of an exercise called ‘Red Team, Blue Team’ in which the red team seeks to uncover “very little unseen flaw, every overlooked potential for harm, every more elegant solution that the blue team missed because they were so in love with their initial idea” 4. This can be both an efficient way to quickly discover the bias embedded into the design output of the team and avoid the pitfalls of falling in love with the wrong idea.

Watch for overly optimistic interpretation of data

A critical eye is necessary during design research. We must be diligent not to interpret data the wrong way, especially if the interpretation favors the desired outcome. When we watch for an overly optimistic interpretation of research findings or design feedback, we can avoid confirming a preexisting bias towards a specific option or approach.

Related

False consensus effect

A pervasive cognitive bias that causes people to see their own behavioral choices and judgments as relatively common and appropriate to existing circumstances.

Observer-expectancy effect

A form of reactivity in which a researcher’s cognitive bias causes them to subconsciously influence the participants of an experiment.

Semmelweis reflex

A metaphor for the reflex-like tendency to reject new evidence or new knowledge because it contradicts established norms, beliefs, or paradigms.

Become aware of your decision frame

In 1981, Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman explored how different phrasing affected participants’ responses to a choice in a hypothetical life and death situation.5 In the study, participants were asked to choose between two treatments for 600 people affected by a deadly disease. Treatment A was predicted to result in 400 deaths, whereas treatment B had a 33% chance that no one would die but a 66% chance that everyone would die. This choice was then presented to participants either with positive framing, i.e. how many people would live or with negative framing, i.e. how many people would die. Treatment A was chosen by 72% of participants when it was presented with positive framing (“saves 200 lives”) dropping to 22% when the same choice was presented with negative framing (“400 people will die”).

The choice of the participants in this study highlights our tendency to make decisions based on whether the options are presented with positive or negative connotations; e.g. as a loss or as a gain. In psychology, this is known as the framing effect and it affects all aspects of the design process, from interpreting research findings to selecting design alternatives.

How it occurs

Framing tends to happen in two ways during design research. Firstly, the phrasing of questions during user interviews or usability tests can have a significant impact on the response of participants. Secondly, how we choose to present research findings. Another potential entry point for framing during the design process is when receiving design feedback. Overly specific feedback can frame up the problem in a way that limits the design solution, or influences it in a way that leads to overlooking other important considerations.

Think through the context

Solutioning when we should be still gathering information can be a constant challenge for team members, especially for designers. While it may be tempting to jump into solutions right away, taking a little more time to think through context will significantly impact how we interpret the data. It’s only once we spend ample time with the gathered data that we can begin to synthesize useful insights from it and identify patterns that aren’t as obvious on the surface.

Gather more context

Instead of making a decision based on however much data you have, wait until you have enough to make an informed decision. Sometimes research uncovers what we need to learn more about. You’ll know you have enough information to make an informed decision when you have a clear idea of the problem and sufficient information to begin on a solution.

Switch your view

Another way to diagnose if your opinion is being influenced by framing is to switch up your point of view. You can do this by reversing a data point from a success rate to a failure rate, or taking the opposite approach to articulating a problem. The point of this is to perceive the data from another angle to avoid emphasis or exclusion of specific information.

Related

Interviewer bias

A bias caused by mistakes made by the interviewer, which may include influencing the respondent in some way, asking questions in the wrong order, or using slightly different phrasing (or tone of voice) than other interviewers.

The Hawthorne effect

A type of reactivity in which individuals modify an aspect of their behavior in response to their awareness of being observed.

Social desirability bias

A type of response bias that is the tendency of survey respondents to answer questions in a manner that will be viewed favorably by others.

We must remember that we’re just as vulnerable to the blindspots and fallacies of cognitive bias as the people who use the products and services we design. Our own bias can creep into the design process if we aren’t being diligent enough to identify and mitigate them upfront. A big part of mitigating this is simply being aware of when and how they can emerge and influence design decisions.

When we consider what we don’t see, we can get a more accurate representation of data and avoid the pitfalls of survivorship bias. When we refrain from building solutions in search of a problem, we can ensure the products and services we do build focus on the actual needs of end-users and dodges the risk of confirmation bias. Finally, we can cultivate awareness of our decision frames to mitigate their impact on design decisions.

Further Reading

Thinking, Fast and Slow

A must-read by Daniel Kahneman for anyone interested in diving deep into the world of cognitive bias.

Designing for Cognitive Bias

An excellent book by David Dylan Thomas explores the logic powering human bias and how to start designing more consciously.

Just Enough Research

This book by Erika Hall is focused on design research but explores how to spot your blind spots and biases during research.

How to Avoid 5 Types of Cognitive Bias in User Research

Cognitive biases can skew user research, leading to design changes that don’t address your customers’ real needs. Build digital products that users will love by mitigating these common biases.

Mangel, Marc & Samaniego, F.J.. (1984). Abraham Wald’s Work on Aircraft Survivability. Journal of The American Statistical Association - J AMER STATIST ASSN. 79. 259-267. 10.1080/01621459.1984.10478038. ↩︎

Hall, Erika (2013). “Just Enough Research”. A Book Apart. ↩︎

Lord, Charles & Ross, Lee & Lepper, Mark. (1979). Biased Assimilation and Attitude Polarization: The Effects of Prior Theories on Subsequently Considered Evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 37. 2098-2109. 10.1037/0022-3514.37.11.2098. ↩︎

Thomas, David Dylan (2020). “Designing for Cognitive Bias”. A Book Apart. ↩︎

Tversky, Amos; Kahneman, Daniel (1981). “The Framing of decisions and the psychology of choice”. Science. 211 (4481): 453–58. Bibcode:1981Sci…211..453T. doi:10.1126/science.7455683. PMID 7455683. S2CID 5643902. ↩︎